You know that feeling when a destination has been hyped up, and you get there, and you’re feeling a bit underwhelmed? Arriving at the tiny spit of land that makes up Chumbe Island, I don’t at first see the soaring air-filled main lodge or the cozy bungalows, both of which are built out of local material, making them camouflaged secrets waiting to be discovered. As the boat approaches, all I see is a scruffy forest on inhospitable fossilized coral rock.

In Your Bucket Because…

- It’s one of the most diverse coral reefs in East Africa, with some species found nowhere else.

- You get inspired by what one person with a vision can accomplish.

- Your stay contributes to a worthwhile project that educates kids and visitors, preserves habitat, and provides environmentally sustainable tourism jobs.

- Good for ecotourists, snorkelers, seekers of peace and quiet.

Chumbe Island is only about a half mile long and 200 yards wide. Sitting in the channel that separates Zanzibar from mainland Tanzania, it has mostly been ignored by history. Until recently, the only visitors have been fishermen, the only human inhabitant a lighthouse keeper. That was until 1997, when Sibylle Riedmiller, a German expatriate, opened an eco-resort with the intention of protecting one of East Africa’s healthiest and most diverse shallow coral reefs.

She, too, was underwhelmed when she first arrived.

“I had been looking for a reef to save,” she told me, back in 1998, when the resort was still under construction, as if saving a reef was a perfectly ordinary item to put on a to-do list. There was no shortage of endangered reefs in Tanzania; what Riedmiller calls the “Wild West of tourism” was in full swing, threatening pristine coral ecosystems with over-development, habitat destruction, and over-fishing. However, finding a reef where it was practical to launch a program was a challenge.

“There was always a problem,” she said. “The reef was too far from transportation to make it viable for tourists. Or a fishing-based economy stood in the way, or there was opposition from the government. Or the problems were too extensive to be addressed by a small project.”

By the time she arrived at Chumbe, she was tired and frustrated and seeing the untended, uninhabited landscape on a gray day did nothing to improve her mood.

“And then,” she said, “I looked underwater.” Riedmiller paused, momentarily and uncharacteristically stumped for words. “The corals, the colors… I just couldn’t believe it. I can’t describe it.”

So I do what she did to see what she saw: I don my mask and look beneath the sea. It’s like I’ve wandered into The Wizard of Oz just exactly when the world turns from black-and-white to color. This Zanzibar reef features one of the world’s most diverse shallow coral gardens, representing nearly all of East Africa’s coral species and more than 370 species of fish. And all of them, it seems, are right here, right now.

This is, it turns out, not only a place that meets expectations — it exceeds them.

Chumbe Island Coral Park Eco-and Resort

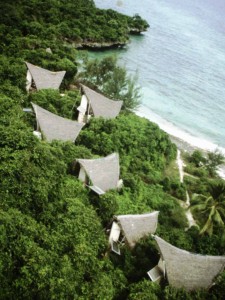

Fast forward to the present day, when Chumbe Island Coral Park is now a part of an award winning eco-resort that has garnered international award and rave reviews from customers. It’s one of the most highly rated resorts on Zanzibar, and the reef Sybille wanted to protect has become a protected marine park. The architecture of the main lodge and the private bungalows features local material such as makuti (palm thatch), coir rope (woven from coconut husk fibers), and poles made from the wood of the native evergreen casuarina tree. The main building is topped by a huge thatched roof that shelters it like an oversize umbrella — and serves the practical function of being part of the water cachement system. Each of the small bungalows contain eco-friendly features that promote recycling, composting waste, and using solar energy. The project also provides jobs for local people and an environmental education program for schoolchildren.

The process hasn’t been easy.

“There were problems from A to zed,” Riedmiller told me, and started naming them: funding shortages, cultural differences, mistrust, government bureaucracy, logistics, geology, and even the weather, which destroyed one of the property’s boats.

Nor did she make it easy on herself: The stated goal of the project was to have zero — ZERO — environmental impact. All the power is solar, all the water is from cachements, foods are locally grown, waste is used as compost, gray water is used for irrigation, and nothing is discharged into the sea.

And the results are spectacular. Nature trails cross the island. Native Zanzibaris have been trained as guides to explain the underwater ecology and assist scientists with species counts and monitoring. Visitors snorkel right off shore, and relax in bungalows that are both protected from nature yet open to it. Time slows to a crawl. And under the sea, the reef lives on, colorful, protected, healthy, and alive.

Practicalities

The accommodations can best be described as upscale eco-rustic. Toilets are composting, and energy is solar. Overnight guests should be sure to have an LED headlamp just in case the solar power goes out. Mosquito nets are provided, but bring bug repellent. If that doesn’t sound like your style, visit on a day trip from Stone Town. Masks and snorkels are available. This is a shallow reef, so while it’s a pristine snorkel site, it’s not a dive site. Note that tides and winds can influence chop and visibility.