I am not thinking about gesyers or fumaroles as I am walking. I am thinking about animals, specifically, about the grizzly bear the ranger told me might be inhabiting this slice of Yellowtone’s backcountry, in the southern section of the park near the Snake River.

I’m also pretty sure I heard a wolf last night: It sounded like a baritone coyote, a long mournful, surprisingly musical song. Whatever it was, there was only one of them, which is not my experience regarding the garrulous excitable coyotes I hear on summer nights back home.

When I see the smoke, I’m jolted back to reality: a campfire? A woodstove in a ranger cabin? Wildfire?

In Your Bucket Because…

- You’ve known what this iconic landscape looks like your whole life.

- Wildlife, geothermal features, mountains, waterfalls, trails, lakes, and camping make this an outdoorsman’s paradise.

- Good for all outdoorspeople and nature lovers, as well as outdoorsy families.

But it is none of those things; instead, it is a backcountry geyser basin. No boardwalks, no signs, no warnings. It takes me by surprise, and I wonder, as I often do when stumbling on surprises in the backcountry, who saw it first, how did they feel, what did they think.

In East Africa, the coastal porters who accompanied Europeans into the interior thought that evil spirits had bewitched the water on Mt. Kenya to turn it into ice. Apparently, the first European explorers here were of a similar mind: They sent home such reports of unbelievable wonder — spouting geysers, herds of animals, petrified forests, bubbling mudpots as though hell had found a portal to earth — that one East Coast newspaper declined to publish a story on the grounds that they didn’t take fiction.

Yellowstone National Park: An American Icon

Yellowstone is iconic in the American imagination: We all have pictures of Old Faithful in our minds, as well as the other geysers and mudpots and fumeroles and steam vents, Artist’s Point, Mammoth Hot Springs, the buffalo, the elks, the grizzly bears. It’s America’s first national park, as well. (To clear up a common point of confusion: Yosemite was designated a park earlier, but was originally under California, not U.S., control. So Yellowstone claims the title of “first.”)

Give credit where it’s due: The men who discovered Yellowstone could have divvied it up, built lodges and railroads, lured tourists, and made fortunes. Instead, they made a park, and started a legacy of parklands that is a model for parks and preservation worldwide. Indeed, our national park system has been called “America’s best idea.”

Hiking Trails in Yellowstone

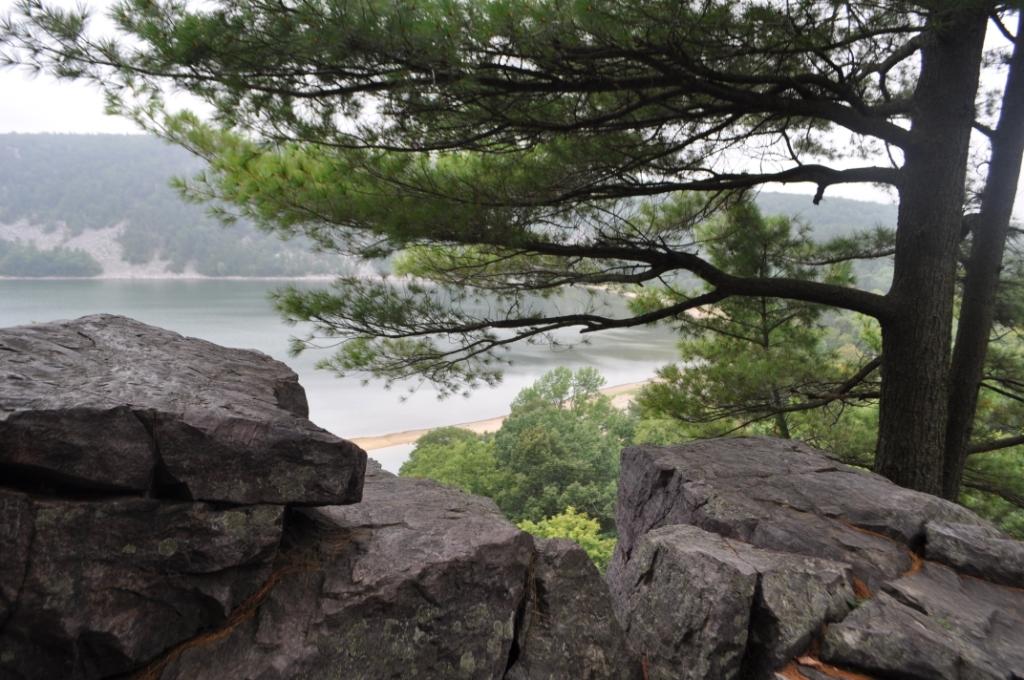

Trails crisscross Yellowstone in all directions, departing into the backcountry from virtually every major campground, giving dayhikers willing to put a few miles on their boots a chance to break away from the crowds.

The difference between front country and backcountry is startling, and, as is true in so many parks, you encounter the change only a mile or two from any trailhead. Two miles in, two miles out is a hefty half-day walk for the average family. Go just a little farther, and traffic drops precipitously till the only people you’ll see are backpackers and the occasional ranger.

The park is 2.2 million acres (about 3450 square miles, somewhere between the size of Delaware and the size of Connecticut), and it contains 1,100 miles of hiking trails, so you’re not going to see it all in one trip, even if you walk across it, which is what I was doing. No matter where you hike, you are foregoing some other place. In addition to its sheer size, Yellowstone encompasses a wide variety of habitats: forests, fields, mountains, river valleys, along with lakes and waterfalls.

So you need to focus on what you want to see, and my advice is to start with the two things that are unique to Yellowstone: its geothermal features and its wildlife.

Geothermal features are found in many places around the park, most conveniently around Old Faithful, where a trail through Upper Geyser Basin leads past a concentration of geysers and mudpots. In the Norris area, you can hike to Artist Paint Pots and Monument Geyser Basin.

Wildlife is a little tricker because animals move seasonally, and even daily: This is something to check at the ranger stations, but a few possibilities include:

- Beaver Ponds Loop Trail in the Mammoth Area (elk, deer, moose, pronghorn)

- Fairy Falls near Old Faithful (elk, buffalo, coyote, bald eagles)

- Observation Points Trail (elk and bison, plus a view of Old Faithful!)

- The Pelican Creek Trail in the Lake area (bison and bird watching)

- The Specimen Ridge Trail near Tower Falls (elk, coyote, bighorn sheep).

Sometimes, of course, the animals show up where you least expect them, like right in the middle of a trail junction. In the Hayden Valley, trails can be hard to find, reputedly because bison knock them down. While there, I encountered some evidence of that, along with a couple of babbling hikers who were trying to tell me about the route ahead, and where to turn: Apparently, the sign was gone, perhaps knocked over by an animal. A lone bison was doing penance for his misdeeds (or the misdeeds of his friends): Standing placidly and apparently immobile at the trail junction, he made for a useful landmark, as the hikers advised me to “turn left at the buffalo.”

Practicalities

- You don’t need a permit for dayhiking, but you do need a permit for overnight camping.

- Even if you’re just day-hiking, check in at the ranger a station to pick up a map and get current advice regarding conditions, especially regarding grizzly bears. Dayhiking trails are frequently closed owing to grizzly activity. If you’re camping, you’ll want information on proper food storage.

- Many hikers bring canisters of pepper spray or bear bells (which announce their presence and supposedly scare animals away).

- The park is much less crowded after Labor Day, but nights get cold.

- If you need more amenities than are available at a campsite, try the historic (and ideally situated) Old Faithful Lodge or head north to Mammoth Hot Springs.

Updated and republished 2018