Walking up the hill to Dover Castle, I expected tales of jousting and medieval brutalities: chain mail and armor, cold old stone, and a torture chamber or two.

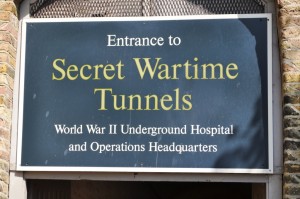

And indeed, there were plenty of old stone walls, and I’m quite certain a dungeon — along with the lighthouse that dates to Roman times and the Church of Mary-in-Castro, a thousand-year-old building from the late-Saxon era. But I found myself intrigued by a sign referencing more modern times: “Entrance to Secret Wartime Tunnels.”

Well, maybe no-so-secret anymore….

In Your Bucket Because…

- The display, complete with flickering lights and a sound-track of conversations that might have taken place, puts you right in the midst of historic events.

- You’ll experience the everyday lives of the men and women who served during the Battle of Britain (and beyond).

- Good for history buffs, particularly those interested in World War II.

The sign led to an overlook where World War II guns stood guard, pointing toward the harbor. Today, the only threat seemed to be an invasion of shore excursionists from the lone cruise chip that sat peacefully in port. Dover overlooks the narrowest part of the English Channel, which means it’s as close as England gets to continental Europe. As a result, the high point atop Dover’s famed white cliffs has been an outlook and a point of defense for more than 2,000 years, according to English Heritage, which operates the property.

But it was the most recent war that intrigued me. I followed the signs to an entrance that led inside the earth, underground to a waiting room where I booked a tour. A few minutes later, I was led into the guts of the cliffs, into a labyrinth of more than three miles of underground tunnels, many of which were first excavated in the late 18th and 19th centuries and served as garrisons during the Napoleonic Wars.

In 1939, these tunnels were converted, first into an air-raid shelter, and shortly after, into a military command center from which Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsey directed the evacuation of French and British soldiers from Dunkirk in May 1940. Code-named Operation Dynamo — and later popularly renamed the “Miracle of Dunkirk” — the desperate retreat brought more than 388,000 soldiers to England to fight another day.

In 1941, the underground headquarters and tunnel system were expanded to house a communications center with telephone switchboard and radio equipment. Ship to shore communications enabled contact with naval vessels that picked up pilots who had been shot down. An underground hospital had also been built, along with kitchens, dormitories, and mess rooms, and pilots were brought here for emergency treatment and stabilization before being send inland.

Experiencing History

I followed a guide into the tunnels, where the silence of the underground was shattered by rumbling, the sound of explosions, and flickering lights. This tour is more “show” than “tell,” and what we were experiencing was what it would have been like to be underground during an air raid. As we walked through the underground field hospital, we saw surgical instruments arranged on a tray, and a gurney with bloodied sheets. Through loudspeakers, we heard the reenacted discussions of medical staff trying to save a pilot while the lights went on and off to the muffled accompaniment of bombs exploding outside.

In other parts of the tunnels, a timed tape loop continued with recorded conversations that might have taken place among soldiers, officer, and nurses. The different sections of the tunnels have been recreated to look as they did during the war: the Command Center with its large maps of Europe, the telephone exchange and repeater stations with their large banks of telephones and telegraph stations, and the anti-aircraft rooms, where German bombers were tracked.

I tried to image living and working down here, encased in the damp, dark rock, surrounded by purposeful bustle. On the sea side tiny windows, looked out over the English Channel.

And in my mind, the tune of the old song, “White Cliffs of Dover,” played. My mental recording was appropriate to the setting: a scratchy-sounding old-timey slightly off-key version of the promise of love, laughter and peace ever after… “tomorrow, when the whole world is free.”

After the end of World War II, the cliffs were readied yet again to be put back into service, in case they were needed to face the new Communist threat.

Plus ça change.

Practicalities

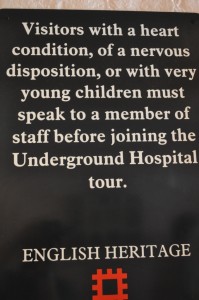

- The tour of the underground tunnels takes about an hour and requires a separate ticket. If there’s a wait, you’ll be assigned a time of entry when you buy your ticket.

- No photos are allowed inside the tunnels

- Two levels of the tunnels (there are known to be five all together, although new sections continue to be discovered) are open to tourists; the others are unexcavated or considered too dangerous.

- There’s a tunnel gift shop with World War II books, model planes, and other memorabilia.

- You can easily walk to the castle from Dover itself; from the base, it’s about a 10 – 15 minute uphill hike.

I was fascinated by the sense of “being there” at the Cabinet War Rooms in London, so this is a definite stop on my next trip.

We visited from the U.S. in 2004, and one of the most interesting aspects of the tour highlighted the women who worked there. They had gone (as is typical of history) largely uncredited for their service and contributions until recently. They also referred to the location as “Dumpee” or something like that? Not finding reference to either online. Any assistance would be great. Thanks!